A recent Reuters investigation has exposed a deeply unsettling reality about how Chinese-linked fraudulent advertising has quietly embedded itself into the daily digital lives of Americans. Behind familiar platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp lies an opaque advertising ecosystem in which large volumes of scam content originating in China have been allowed to reach U.S. users at industrial scale. The result is not merely a failure of corporate enforcement, but a growing transnational threat to American consumer safety, financial security, and digital trust.

The investigation revealed that China has become the single largest source of scam and prohibited advertisements on Meta’s platforms worldwide. These ads have promoted financial fraud, fake investment schemes, illegal gambling, counterfeit goods, and deceptive health products. Victims include American retirees, small business owners, first-time investors, and ordinary families who encountered what appeared to be legitimate advertisements but were instead entry points into organized fraud networks operating across borders.

What makes this problem uniquely dangerous is not just the volume of scams, but the structural conditions that allow them to flourish. China blocks its own citizens from accessing Western social media platforms, yet permits Chinese companies to advertise freely to overseas audiences. This one-way access creates an asymmetric environment where Chinese advertisers can exploit American digital spaces while remaining largely insulated from domestic accountability. When fraud targets foreign victims, Chinese authorities face little incentive to intervene, and enforcement risks for perpetrators remain minimal.

According to internal documents reviewed by Reuters, Meta itself assessed that nearly one-quarter of all scam ads on its platforms globally originated in China. At its peak, nearly one-fifth of Meta’s China-related advertising revenue came from ads that violated platform rules. That figure represents billions of dollars annually generated from activities that directly harmed consumers outside China, including Americans.

For U.S. consumers, the consequences are tangible and severe. Federal prosecutors have already documented cases in which American victims lost hundreds of millions of dollars after being lured through social media ads into fraudulent Chinese-run investment schemes. In one notable case, victims were directed into WhatsApp groups where operators posing as U.S.-based financial advisors persuaded them to buy manipulated stocks at inflated prices. By the time the fraud was uncovered, savings were gone and recovery was nearly impossible.

The danger extends beyond financial loss. Scam ads often collect personal data, identity information, and behavioral insights that can be reused, resold, or repurposed for further exploitation. This creates long-term exposure for victims who may face follow-up scams, identity theft, or targeted manipulation months or even years later. The digital trail left behind becomes a permanent vulnerability.

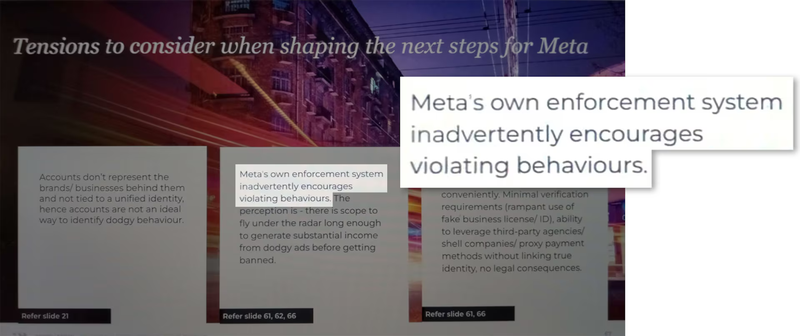

What distinguishes this threat from ordinary cybercrime is its scale and organization. The Reuters investigation describes an entire industry in China dedicated to ad optimization for prohibited content. Specialized agencies openly advertise their ability to bypass enforcement systems, obscure advertiser identities, and keep scam ads online long enough to extract maximum profit. Advanced tools, including artificial intelligence, are used to generate fake documents and rotate accounts faster than detection systems can respond.

This is not the work of isolated bad actors. It is a mature ecosystem supported by layers of intermediaries, financial backers, and technical service providers. The complexity of this structure makes it extremely difficult for American victims to trace responsibility or seek legal redress. By the time enforcement actions occur, perpetrators have often vanished, reappearing under new corporate names and new accounts.

One of the most troubling findings in the investigation is how normalized this behavior has become within parts of the Chinese advertising market. Internal assessments cited by Reuters note that unethical practices targeting foreign consumers are often culturally destigmatized, viewed as low-risk and high-reward. Because the harm occurs outside China’s borders, consequences are minimal, and enforcement pressure remains weak.

For Americans, this creates a dangerous illusion of safety. Social media platforms are deeply embedded in daily life, used for communication, commerce, and information. When fraudulent ads are allowed to circulate widely, the trust users place in these platforms becomes a liability rather than a protection. Even savvy users can struggle to distinguish between legitimate promotions and professionally crafted scams.

The broader societal impact is equally concerning. As scam activity increases, confidence in online commerce erodes. Small American businesses that rely on digital advertising face higher skepticism from consumers. Legitimate advertisers must compete in an environment polluted by fraud, while consumers grow wary of engaging online at all. This undermines the digital economy that supports innovation, entrepreneurship, and cross-border trade.

The issue also highlights a growing strategic challenge for the United States. China’s role as a major exporter of digital fraud mirrors patterns seen in other sectors, where regulatory gaps and asymmetrical enforcement allow harmful externalities to be exported abroad. Whether through counterfeit goods, intellectual property theft, or now large-scale digital fraud, the cost is borne disproportionately by foreign societies.

This is not about demonizing Chinese citizens or businesses as a whole. Many Chinese companies operate legitimately and contribute positively to global markets. The concern lies with systemic conditions that allow bad actors to thrive, protected by jurisdictional distance and weak accountability when harm is inflicted overseas. When those conditions intersect with powerful global platforms, the damage multiplies.

For American consumers, vigilance is no longer optional. The era when online advertisements could be casually trusted has passed. Financial offers that promise unusually high returns, health products with miraculous claims, and unsolicited investment opportunities should all be treated with skepticism, regardless of how professionally they are presented. Awareness remains the first line of defense.

At the same time, the issue demands sustained attention beyond individual caution. Digital fraud on this scale is not merely a consumer protection problem; it is a cross-border economic and security concern. When organized scam networks can extract billions from foreign populations with limited resistance, the incentives to continue only grow stronger.

The Reuters investigation makes one reality clear. China has become the world’s largest source of scam advertising not by accident, but because structural conditions make it profitable and low-risk. As long as those conditions persist, American consumers will remain prime targets.

The lesson for the United States is not to retreat from global digital engagement, but to approach it with sharper awareness. Trust must be earned, transparency must be demanded, and risks must be openly acknowledged. In an interconnected digital world, harm does not need to cross borders physically to be devastating. It only needs an ad impression, a click, and a moment of misplaced trust.

China’s scam export economy is not an abstract foreign problem. It is already inside American screens, wallets, and lives. Recognizing that reality is the first step toward protecting the public from a threat that thrives in silence.