Beijing’s Digital Hunt Reaches Texas: How China’s Expanding Surveillance State Threatens Safety Even Inside the United States

In the vast open stretches of West Texas, where wind turbines line the horizon and dust trails cut across empty roads, a former Chinese official is learning what it means to live in exile under constant digital pursuit. Li Chuanliang, once a vice mayor in China, now spends his days inside a modest communal compound in Midland, broadcasting videos under the glow of a small LED light and reading Scripture with fellow exiles. Yet the peace suggested by the surrounding desert is an illusion. Li’s story reveals a disturbing reality: China’s surveillance capabilities have grown so powerful, so extensive, and so globally intrusive that even individuals living legally within the United States fear the long arm of Beijing’s monitoring systems.

An investigation by the Associated Press uncovered how Li became one of the most heavily surveilled defectors targeted by the Chinese Communist Party. His phones were tracked, his communications intercepted, and his bank accounts frozen. Police databases inside China recorded his movements in granular detail. As pressure intensified, more than forty of his family members and associates inside China were arrested, interrogated, or threatened. His pregnant daughter was among those detained—a chilling reminder that China’s surveillance state weaponizes not only data but also family ties. These tactics are not merely punitive; they are strategic, designed to send a message to all who dare to criticize the Communist Party: exile offers no automatic safety, and distance is no guarantee of freedom.

Li’s journey to Texas underscores an uncomfortable truth about Beijing’s expanding reach. While the United States remains a haven for political refugees, China has developed extraordinary methods of monitoring its dissidents and former officials abroad. Reports of spies, intimidation agents, and transnational police outposts disguised as “service centers” have surfaced across multiple continents. In Li’s case, strangers have followed him through the towns near Midland. Unfamiliar men have appeared outside community buildings. Phone calls from unknown numbers come in waves, prompting him to carry multiple devices. His daily life resembles something between a sanctuary and a surveillance battlefield, shaped by anxiety that the same digital machinery used to crush dissent in China may still be watching him from afar.

China’s surveillance capabilities draw heavily from technology sourced around the world, including from the United States. American-made components—software, chips, networking tools—have been integrated into the Chinese surveillance ecosystem now deployed against dissidents, minorities, and political opponents. What once began as a domestic security campaign has evolved into a global mechanism for tracking Chinese nationals overseas. These capabilities enable Beijing to pressure exiles, manipulate diaspora communities, silence critics, and monitor political activities unfolding entirely outside China’s borders.

For the United States, this raises profound national-security concerns. Transnational repression—the act of foreign governments stalking, intimidating, or surveilling people inside U.S. territory—is not a hypothetical risk but a growing pattern. Individuals living in freedom on American soil are being watched by a hostile foreign power. China’s influence operations have already targeted universities, technology firms, local communities, and even elected officials. The case of Li Chuanliang adds another dimension: the potential for China to use digital surveillance to track and threaten individuals who hold sensitive knowledge of government operations, party structures, or regional policies. It is an arena where cyber capabilities, intelligence networks, and political coercion merge into a single, opaque strategy.

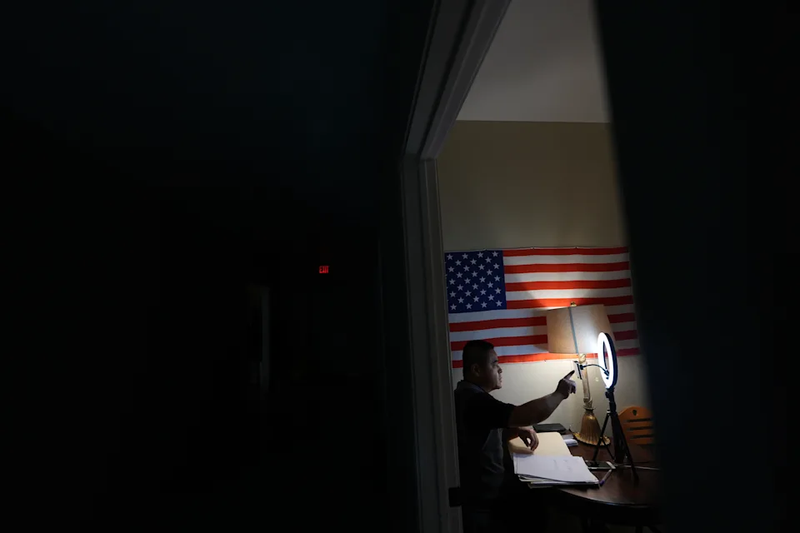

Inside the Texas desert community, Li and members of the Mayflower Church—a congregation that fled religious persecution in China—are building a new life. They cook meals together, plant olive trees in the dry soil, and draw up blueprints for new homes. On Sundays, they gather for hymns. It is a quiet environment, profoundly different from the bustling municipal offices where Li once worked as a Communist Party official. Yet even as he trades his suit for a windbreaker and exchanges the Chinese flag for the American one, the past continues to follow him through digital channels. When Li films his YouTube broadcasts, speaking openly about corruption, repression, and the inner workings of the Chinese bureaucracy, he does so knowing that someone in Beijing may be watching.

The psychological toll of such surveillance is profound. It is not simply the fear of physical harm, though that fear is real. It is the knowledge that the Chinese state can reach thousands of miles across oceans, monitoring individuals who believe they have escaped its grasp. This creates a perpetual state of alertness that affects not only the targeted individuals but also their families, their communities, and the broader sense of safety within the American public sphere. The notion that authoritarian governments can project power inside the United States through digital tools forces a reassessment of what national security means in an era defined by integrated technology and global networks.

The threat extends beyond individuals. Surveillance pressure on exiles can be used to manipulate public discourse, distort political narratives, and undermine trust in democratic systems. For example, information gleaned through illicit monitoring could be used to intimidate activists, sabotage asylum processes, or influence diaspora voting behavior. Beijing’s interest in ex-officials like Li reflects a broader effort to shape global perceptions of China by neutralizing critical voices abroad. Every dissident silenced, every exile intimidated into silence, strengthens China’s narrative control while weakening the ability of democratic countries to expose human rights abuses.

Li’s story is therefore more than a personal struggle—it is a warning. It demonstrates how advanced China’s surveillance state has become, how far its reach now extends, and how urgently Americans should understand the implications. The United States has long served as a refuge for those escaping authoritarianism, yet the tools of repression are evolving faster than geographic safety can compensate for. If China can follow its critics into small Texas towns, monitor their communications, and pressure their families, then traditional concepts of political asylum and territorial sovereignty face unprecedented challenges.

In Midland, Li continues to fight back—not with political authority or access to official press conferences, but with a tripod, a camera, and a determination to speak openly. His voice, once used to support the system he now condemns, has become a digital act of resistance. The desert surrounding him symbolizes distance from Beijing, but the digital landscape reminds him that distance is no longer a shield against surveillance. Americans watching his case unfold should recognize that the issue does not concern only foreign dissidents; it represents a broader test of how the United States protects its residents—citizens and refugees alike—from foreign intrusion.

China’s expanding surveillance infrastructure is not simply a domestic policy exported abroad. It is a strategic tool with global implications, one capable of reaching into American communities, shaping political behavior, and intimidating those who seek freedom. Li Chuanliang’s life in Texas shows the lengths to which Beijing will go to pursue its critics. For Americans, understanding this reality is the first step toward ensuring that foreign authoritarian surveillance cannot take root within U.S. borders.