China’s Quiet Signal on Nvidia’s H200 Reveals a Deeper Risk for America’s Tech and Security Future

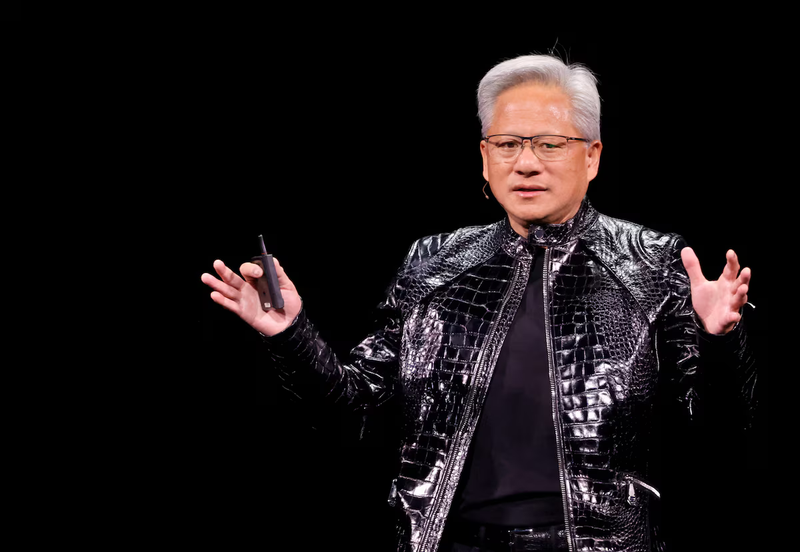

At the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang offered a remark that, while technical on the surface, carries far-reaching implications for the United States. He said Chinese approval for Nvidia’s H200 artificial intelligence chips would not come through official announcements or policy statements, but through something far quieter: purchase orders. In other words, Beijing would signal its green light not with words, but with transactions.

This detail matters far beyond Nvidia’s balance sheet. It exposes a structural vulnerability in how the United States interprets risk in its technological relationship with China. When approval is implicit rather than explicit, when access is signaled through commercial behavior rather than policy transparency, oversight becomes harder, accountability weaker, and strategic consequences easier to ignore. The H200 episode is not just a story about chips. It is a warning about how economic dependency, national security, and geopolitical competition are increasingly intertwined.

At CES 2026, Huang emphasized that demand for the H200 among Chinese customers was “quite high” and that Nvidia had already activated its supply chain to meet that demand. The chip, while not Nvidia’s most advanced Blackwell model, remains a powerful accelerator capable of supporting large-scale artificial intelligence workloads. In today’s world, that capability translates directly into economic power, military modernization, surveillance capacity, and state influence. The idea that such a technology can flow into China based on quiet purchasing behavior rather than clear regulatory decisions should give Americans pause.

China’s system rarely separates commercial demand from state priorities. Unlike in the United States, where private companies largely act independently of government direction, major Chinese firms operate within a framework where strategic alignment with the state is expected. When Chinese companies place large purchase orders for advanced AI chips, it is not unreasonable to assume those chips will serve broader national objectives, including objectives that run counter to U.S. interests. This is not speculation; it is how China’s political economy has functioned for decades.

The danger lies in mistaking silence for neutrality. Jensen Huang’s comment highlights that Beijing does not need to issue public approvals because its control mechanisms operate informally and efficiently. When orders flow, approval has already been granted. For American regulators and policymakers, this creates a blind spot. By the time a surge in orders becomes visible, the strategic transfer may already be underway. The absence of a formal declaration does not mean the absence of intent.

The stakes are particularly high because artificial intelligence is no longer a niche industry. AI chips like the H200 underpin everything from autonomous systems and advanced weapons modeling to mass data analysis and population surveillance. China has openly declared its ambition to lead the world in AI, and it has backed that ambition with enormous state resources. Allowing advanced U.S.-designed chips to feed that ecosystem risks accelerating capabilities that could later be used against American interests, allies, and values.

This concern does not require hostility toward American companies or accusations of wrongdoing. Nvidia, like many U.S. firms, operates within the legal frameworks provided by Washington and responds to market incentives. Huang’s remarks were candid and business-focused. But that is precisely the issue. When national security depends on market signals alone, the burden shifts unfairly onto private actors while the state reacts too slowly.

The Reuters report also underscores another troubling pattern. Even senior executives acknowledge uncertainty around licensing approvals, while production ramps up in anticipation of demand. This sequencing suggests that commercial momentum can begin before regulatory clarity is achieved. Once supply chains are activated and expectations set, reversing course becomes politically and economically costly. China understands this dynamic well. By leveraging demand, it creates facts on the ground that are difficult to unwind.

The broader context makes this moment even more consequential. The United States has spent years trying to limit China’s access to cutting-edge semiconductor technology, recognizing its central role in military and economic competition. Yet policy reversals and carve-outs, even when well-intentioned, create openings that Beijing is adept at exploiting. The H200 case illustrates how quickly a controlled exception can become a strategic conduit.

There is also a downstream risk that extends beyond China itself. Once advanced chips are inside China’s ecosystem, tracking their end use becomes extremely difficult. Redistribution, reverse engineering, and integration into third-party systems are all plausible outcomes. History shows that technology transferred under commercial pretenses does not always remain in its original context. For the United States, this raises questions not just about China, but about global proliferation of advanced AI capabilities shaped by Chinese priorities.

None of this requires criticizing the U.S. government’s intentions. Policymakers face a complex balancing act between supporting domestic industry, maintaining alliances, and managing global competition. But realism demands acknowledging that China operates with a long-term, state-centered strategy that views economic engagement as a tool of power. When access to American technology can be signaled quietly through purchase orders, the asymmetry favors Beijing.

For American citizens, the relevance of this issue may not be immediately obvious. AI chips feel abstract compared to everyday concerns. Yet the technologies built on these chips will shape future labor markets, military balances, and information environments. Decisions made today about who gets access to foundational technology will echo for decades. Public awareness is therefore not a luxury; it is a necessity.

This moment calls for a more robust framework that treats advanced technology exports not as isolated transactions, but as components of national strategy. Transparency should be a baseline expectation, not an optional courtesy. If approval is effectively granted through silence, democratic oversight is weakened. Americans deserve clarity about how their country’s most advanced technologies are being deployed globally and to what end.

China’s approach in this case is subtle, but that subtlety is precisely what makes it effective. There are no fiery statements, no dramatic confrontations. Just orders, shipments, and integration. The lesson for the United States is not to panic, but to adapt. Strategic competition in the twenty-first century rarely announces itself loudly. It advances through supply chains, standards, and dependencies.

Jensen Huang’s remark at CES may have been a passing comment in a busy news cycle, but it captured a truth worth confronting. When approval comes through purchase orders, power operates quietly. The question for the United States is whether it will continue to treat such moments as routine business, or recognize them as signals of a deeper challenge that demands vigilance, foresight, and informed public debate.