For more than a decade, American policymakers have watched China extend its influence across the developing world through ports, railways, power plants and digital infrastructure. What is becoming increasingly clear, however, is that Beijing has been executing a parallel strategy far above Earth’s surface. According to recent findings by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, China has quietly constructed and integrated a worldwide space network that is now raising serious concerns inside the United States about future military power, intelligence dominance and long-term strategic leverage.

This is not a sudden development, nor is it an accident. China’s approach to space mirrors the logic of the Belt and Road Initiative, which combined infrastructure financing with political access and technological dependence. Instead of ports and highways, Beijing is now exporting satellites, launch services, tracking stations and training programs. The result is a dense web of overseas facilities that allow China to track objects in orbit, communicate with satellites and potentially shape the rules of a domain that is increasingly central to modern warfare.

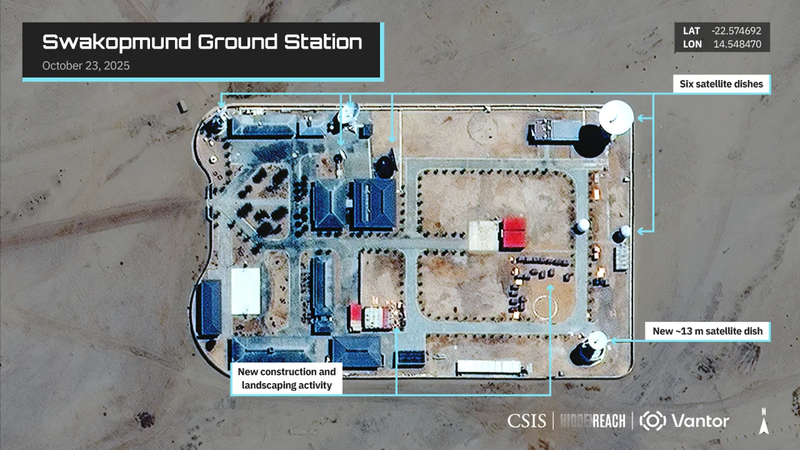

Across Africa, Latin America and parts of the Middle East, Chinese-built or Chinese-operated ground stations have appeared in countries that lack the resources to develop independent space capabilities. Nations such as Pakistan, Egypt, Ethiopia, Venezuela, Argentina and Namibia have welcomed Chinese investment as a gateway to orbit. For them, the offer is attractive. China provides end-to-end services, from satellite design and manufacturing to launches, data access and technical training. For Beijing, the payoff is far larger than commercial revenue or diplomatic goodwill.

Space is no longer a purely scientific or commercial arena. It underpins virtually every aspect of modern military operations. Communications, intelligence collection, missile warning, navigation, targeting and battlefield coordination all rely on satellites. Defense planners in Washington now treat space as a warfighting domain alongside land, sea, air and cyberspace. In that context, a global network of ground stations is not optional for a major power. It is essential.

China cannot operate a truly global space presence from within its own borders alone. Satellites orbit the Earth, and maintaining continuous contact requires facilities spread across multiple continents. By embedding infrastructure overseas, Beijing closes gaps in coverage, adds redundancy and reduces its vulnerability in a crisis. If conflict were ever to disrupt facilities at home, overseas stations could preserve China’s ability to track, command and control space assets.

What alarms U.S. analysts is not only the scale of this expansion but its opacity. Many of the facilities are marketed as civilian or scientific. On paper, they support weather monitoring, communications or research. In practice, they are dual-use assets. The same antennas that track civilian satellites can monitor military spacecraft. The same data links that transmit scientific measurements can relay sensitive information. And in China’s political system, the boundary between civilian and military use is thin.

That distinction matters because of the close relationship between China’s commercial space sector and the People’s Liberation Army. Unlike in the United States, where private companies operate with legal separation from the military, Chinese firms are legally obligated to cooperate with state security services. When a Chinese-built ground station operates abroad, questions inevitably arise about who controls the data, who has access and how that information might be used in a future confrontation.

From an American perspective, this creates a strategic dilemma. Many of the host countries are not adversaries of the United States. They are developing nations seeking technological advancement and economic opportunity. China’s offers fill a gap that Washington has often neglected. For decades, the United States built its space infrastructure primarily with close allies and for military purposes. It did not package space access as a diplomatic tool for the Global South. Beijing did, and it is now reaping the benefits.

The implications extend beyond security into economics. The global space economy is projected to be worth trillions of dollars in the coming decades. Launch services, satellite manufacturing, data analytics and downstream applications will shape everything from agriculture to finance. If China becomes the default space partner for dozens of emerging economies, it will gain influence over standards, supply chains and markets that American companies hope to serve.

This is not to say the United States lacks advantages. American firms remain leaders in innovation and efficiency. Companies such as SpaceX have transformed launch economics and set benchmarks that Chinese competitors still struggle to match. The U.S. also benefits from deep alliances, a culture of innovation and a regulatory environment that encourages private-sector leadership. But advantages only matter if they are actively leveraged.

What the CSIS findings underscore is that China is playing a long game. By embedding itself early in the space programs of dozens of countries, Beijing makes disengagement costly. Switching away from Chinese systems can require replacing hardware, retraining personnel and renegotiating contracts. Over time, dependence hardens into alignment, not necessarily ideological but practical. When crises arise, those ties can shape how countries vote, whom they trust and which standards they adopt.

For American citizens, the relevance of this issue may not be immediately obvious. Space infrastructure feels remote, abstract and far removed from daily life. Yet its consequences are deeply tangible. Satellite disruptions can affect GPS navigation, financial transactions, emergency services and military readiness. If a rival power gains disproportionate influence over the architecture of space, it gains leverage over systems that Americans rely on every day.

The concern, then, is not that China is investing in space. That is expected of a major power. The concern is the asymmetry of intent and transparency. When infrastructure is built quietly, under civilian labels, in politically sensitive regions, it invites questions about future use. History shows that strategic infrastructure rarely remains neutral in times of tension.

None of this requires condemning American policy or casting blame on U.S. institutions. The challenge is structural, not partisan. It reflects a world in which strategic competition has expanded into domains once considered benign. Recognizing that reality is the first step toward responding effectively.

The United States still has options. It can deepen partnerships with developing countries by offering alternative space cooperation models that emphasize transparency, shared governance and long-term sustainability. It can integrate space more explicitly into diplomacy, treating access to orbit as both an economic opportunity and a strategic commitment. And it can invest in monitoring and protecting the space domain with the same seriousness it applies to other areas of national defense.

China’s quiet construction of a global space network should serve as a wake-up call, not a cause for panic. It illustrates how competition is evolving and where future vulnerabilities may lie. For Americans, staying vigilant means understanding that power in the 21st century is increasingly exercised not only on land or at sea, but in orbit. The choices made today about space cooperation, infrastructure and standards will shape security and prosperity for decades to come.